Forward Thinking… Daily carbohydrate periodization for athletes (part 1)

Among the most interesting, exciting, and perhaps groundbreaking areas of sports nutrition over the past ten years or so has been the research looking at the strategic manipulation of carbohydrate intakes in order to maximize both training adaptations and racing performance. The purpose of this article is to introduce you to the idea of managing your carbohydrate intake on a day-to-day basis, explain a bit about why it works, and show you ways to implement these concepts.

Carb-loading before a big race is common practice, whether it’s an Ironman triathlon or just a 5k turkey trot, and has long been shown to improve performance. At the same time, a growing number of people are advocating a lower-carb, higher fat approach to fueling endurance exercise. This is due to the increased ability to burn fat and spare muscle glycogen (stored fuel). Listening to both sides of this discussion, nearly anybody would be confused. Well who’s right? It turns out that both sides are… in a way.

Exercising on a low-carb, high-fat diet can indeed confer benefits such as an increase in mitochondrial enzyme activity and an improved ability to burn fat. However, despite these favorable changes, fat-adaptation strategies typically fail to provide any benefit during high-intensity (i.e. race-pace) performance (1). This is likely because the muscle glycogen isn’t actually being “spared”, but rather the athlete is able to burn the stored carbohydrate less effectively.

As it became clear that low-carb diets were generally of little added benefit to exercise performance, the next step many people took was to follow a “train-low, race-high” approach. This meant following a low-carb, high-fat diet for training and then racing on a higher carb intake, usually after a day or two of carb loading. Unfortunately this didn’t work so well either. It turned out that high-fat diets rapidly down-regulate the enzymes involved in burning carbs (which are needed at high intensity), and so carb-loading before a race couldn’t fully restore high-intensity exercise capacity (2).

_

“despite these favorable changes, fat-adaptation strategies typically fail to provide any benefit during high-intensity performance”

_

So what’s the answer?

“Fueling for the work required” is the term often used (3), and seems to be the most prudent and sensible approach. But before you can follow that advice, you need to understand what it actually means!

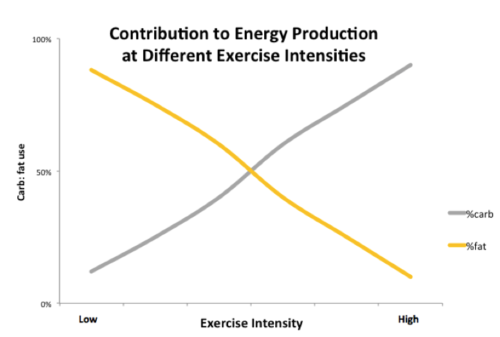

While there is a fair degree of inter-individual variability, this graph gives a general idea of where our energy comes from at varying exercise intensities by showing the relative contributions of both carbs (grey line) and fat (yellow line). When we are sedentary we get a higher percentage of our energy from burning fat (the left side of the graph), and as we start increasing our exercise intensity by walking, jogging, running, sprinting, etc., carbohydrates become responsible for an increasing proportion of our energy production. This is because carbs can be burned without oxygen (anaerobically), providing a faster (and more efficient) source of energy than fats, which require oxygen to be burned.

You should now be able to surmise that a low-intensity, long duration bike ride will rely more heavily on fat burning while a high-intensity interval workout will be fueled primarily by carbohydrates. This is very important to understand because if you try to do a high-intensity workout with a depleted gas tank (as would occur on a low carb diet) then your performance will suffer. On the other hand if you’re doing a long-duration, low-intensity ride then there is not a great need for a large bowl of oatmeal before the workout, or gels, sports drinks, etc., on the bike. In either case, this fueling mismatch will prevent your body from maximizing the workout adaptations.

Practical Application

At the most basic level, simply having a low-carb breakfast and only drinking water (or water plus electrolytes) during low-intensity, long duration workouts can help to maximally stimulate the adaptations in aerobic energy production that occur. In contrast, if you have an interval workout or hard group-ride, this is the time to start with a full tank of gas (fueled up with carbs), and even take in sports drinks, gels, etc. during the workout if it’s longer than about 90 minutes. You will be able go faster, which will lead to better training adaptations while improving your body’s ability to burn carbs at very high heart rates (which is a good thing, contrary to what some might say) (4).

_

Fuel for the work required by reducing carbohydrate intake prior to and during lower intensity workouts. When the goal of the session is to complete the highest workload possible, adequate carbohydrate should be provided before and during exercise.

_

Now, with that being said there is some benefit in doing a high-intensity workout in a glycogen depleted or fasted state. There is a lot of nuance here, and this will be discussed in subsequent posts.

Part 2

The next article will take things a step further, discussing how to think about your carb intake in relation to a) the workout you just had, and b) the next workout you have coming up. This matters because beyond the exercise itself, the availability of fuel to your muscles (or lack thereof) is also a signal to drive adaptations. For example, leaving an empty gas tank overnight while you sleep, rather than always refueling with carbs after a workout, may be surprisingly beneficial (5).

Have you used this approach in your own training? I’d love to hear about your experiences, leave a comment below! To be notified when the next post comes out, leave your email at the top right-hand side of this page!

* I would like to express my appreciation to the venerable sports nutrition researchers tackling this topic in labs across the world, including Drs. Close, Morton, Burke, Stellingwerff, Hawley, and the many others who are leading the way and pioneering what I think will change the shape of interactions between sports dietitians and sport coaches.

** This is a complex and nuanced topic that is still being researched, but I want to offer a practical overview and share some examples of how to use these approaches in your own training. I recently spoke about this on a Sigma Nutrition podcast, and if you’re interested in a more in-depth look at the mechanisms at play this is a very nice article to check out.

Do you want to SUPERCHARGE your training and PR your next race?

Sign up here and get access to an exclusive video showing you EXACTLY how to create your own weekly fueling plan that adjusts carb intake based on your training. I even give you MY EXACT TEMPLATE to work from with step-by-step directions on how to use it. Totally free.

Thanks, Jeff. Your explanation was clear and easy to understand.

Thanks Jaycee, glad you found it helpful!

Excellent commentary about a very confusing subject. Thank you for sharing this information.

Thanks Corey, glad you found it helpful!

Awesome article to clear the much of the muck.

Thanks Nick!

Hi Jeff,

First of all, thanks for your awesome articles, it’s clear and very helpful.

I did my 3 ironmans on a low-carb high-fat diet with carbs loading during last 2 days before race + 2-3 carbs bars during race (I don’t really feel the need to eat a lot). I understand the concept of low vs high intensity for muscles fueling and I often suffer from lack of power during training when I am on a LCHF diet. By the way, that lack of power seems to be less important after some weeks of LCHF diet.

Do you think Ironman pace is low intensity enough to have maximum results with LCHF diet or do I need to use a “normal” diet ?

I am not really satisfied with half Ironman results (I feel a lack of power on the bike for example) but my Ironman results are really good (top 50 in Kona around 9h). As I’ve never done an Ironman with a “normal” diet, I am not sure it will be better for me and I am scared to “try” that during an Ironman.

Thanks for advance.

Hi Guillaume,

Thanks for your comment, and glad you find the articles useful! I think the science strongly supports a higher carb approach for someone completing a ~9 hr Ironman, and definitely for a 70.3. While carbing up for 2 days is a good thing, you’ve down-regulated your ability to effectively use carbs and that doesn’t get reversed in 2 days.

Interesting stuff to read. Keep it up.

Hi Jeff. Just ran into you on Mike Nelson’s podcast. Thanks for sharing your experience, story, and suggestions.

Any thoughts about protein conversion to carbs a la carnivore could do the trick with carb replacement? And also being in keto zone?

Enough protein intake, if there’s an equal gram conversion (1gm protein to 1gm carb) could do something.

Btw, I’m over in NZ, since 2013, from NY. Welcome ;D