Are you matching your fuel with your training?

It makes sense to eat more on days when you’re training more (longer and/or more intense training) and eat less on easier or off days. This has become known as fueling for the work required, or carbohydrate periodization.

But how much more?

Some people might add a small potato, while others might interpret ‘more’ to mean a giant bowl of pasta with 3 bananas for dessert.

And what if it’s an easy ride but a really long one?

Or a hard, but short, workout?

Knowing how much to vary your intake is one of the most under-appreciated aspects of fueling for endurance training.

In this post I will share how I think about and apply these ideas in my daily practice with athletes ranging from ranging from weekend warriors to World Champions. This is based on a combination of 10+ years of experience and iteration, the latest scientific research, as well as my own research (published, unpublished, and in progress).

In one of the studies from my PhD, 55 endurance athletes tracked their diet and training daily for 12 weeks. This meant I could gain insights looking at the relationship between diet and training across over 4,000 days of training, something I don’t think anyone has done before.

Before we start, I should also mention that these practices become more relevant as your weekly training volume increases. If you’re training less than about 7 hours per week, I don’t think you need to worry too much about adjusting your intake on a daily basis (although it wouldn’t hurt).

I have written previously about carbohydrate periodization (part I and part II), this post will talk about how to take the guesswork out of matching your intake with your training!

The basic idea

With a consistent measure of dietary intake and training load, we can see how well dietary intake changes based on your expenditure.

Track your diet

Some people do this regularly, others (like myself) find it quite tedious and not enjoyable. However, there’s not too many ways around this except to say that you can just focus on tracking daily carbohydrate intake and not worry about the other stuff (protein/fats). Also, this doesn’t need to be forever, but tracking for at least 1-2 weeks can provide a nice overview.

Track your training

We need a measure of training load to know how much exercise you’re doing. This can be as simple as duration or distance, but it would be much better to use something like TSS (which you can get for free if you use Training Peaks, Strava, or others). I’m current performing a lab-based study looking at different training load measures which I’ll write about when it’s done, but for now I’d say you can use any measure of training load but TSS is probably best in this context.

Put it together

This is where the fun is! After you’ve accumulated at least several days of tracking both diet and training, we can create a plot and see how it looks.

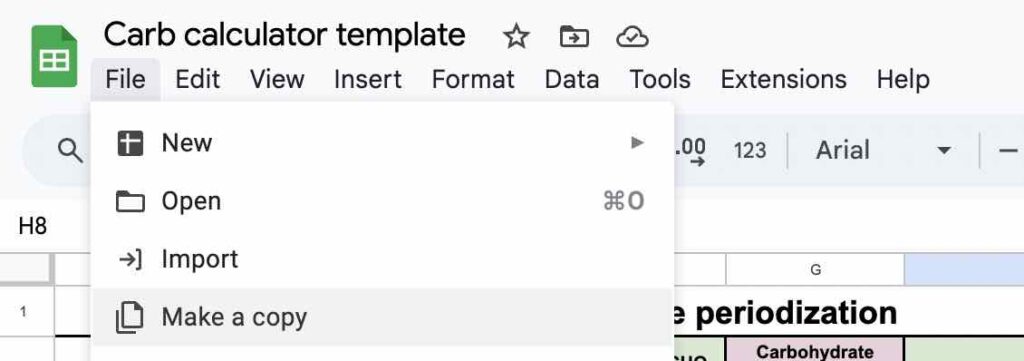

I’ve created a free Googlesheets template which you can use forever (make a copy first).

It comes loaded with example data which I will use this to walk through the components.

- Delete everything in columns B, C, and F, and change the starting date (cell I2) to your desired date.

- After tracking your carbohydrate intake for at least 5 days, enter your data into column F. Enter the total TSS from your workouts into column B (using columns C and D as needed for multiple workouts on the same day).

- Your ‘matching score’ tells you how tightly your intake is being adjusted based on your training load (-100–100%; higher is generally better, but there are caveats).

- The black line shows the ‘trend’ between your intake and training load. To plan your intake to be closer to the line, enter your TSS for the day and look at column G (carbohydrate target).

- Important note – Tightening your intake up to the trend line works if you are already fairly close (matching score of 40-50% or higher. If you are below that, the line won’t be very helpful and we should talk.

Now you have a tool that can provide an objective look at your day-to-day- periodization, and also provide target values based on your typical intake ranges.

To chat more about this and to see what further steps you can take with your nutrition, you can schedule a free 15-min call with me.

I also highly recommend you check out the Hexis app, which is amazing and they keep adding more and more cool features.

Addendum

Based on some questions I want to clarify a few things –

The numbers that come pre-loaded on the googlesheet are purely illustrative examples. The right amount of carbohydrate for you on rest days and in relation to training load will vary. I like this approach of tracking first because it starts from where people are currently choosing as their intake, and we can go from there. Fitter athletes will burn more calories during exercise, so the “CHO (g) for each additional unit of TSS” will be higher.

Carbohydrate intake before and during exercise will influence fat oxidation (see my paper and video here). Sometimes we care about this, and there are strategies which differ based on the goals of each workout. However, this is addressing a different part of the picture than what this daily intake calculator is showing us. Both are important, but one tool can’t address everything.

What about the lagging effects of an athlete ‘catching up’ on easier days? I think this is extremely common yet not ideal and a key part of why this is relevant. To use an analogy, imagine eating all of your daily calories at dinner – you can be in a calorie balance each day but it’s not ideal (the area of within-day energy balance research showed us this). Similarly, if someone eats the same amount of kcal/carbs each day, they may be in a balance at the end of the week but it’s similarly not ideal.